The Victorian corset remained basically similar to the earlier stays in that it accentuated the bosom; but the Victorian corset also minimized the waist by producing a curved hour-glass silhouette - it no longer ended at the hips, but flared out and ended several inches below the waist, - a shape that is even now considered typical both for corsets and for Victorian fashion.

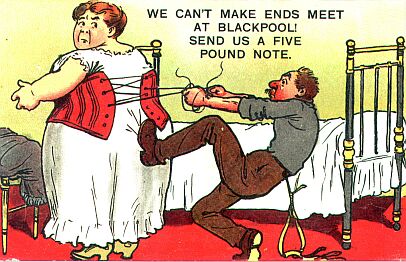

The corset still laced up the centre-back to achieve the correct degree of tightness to fit the wearer’s figure, thus the term “tight lacing.” The new early Victorian fashion of the 1840s and 50s was for curves, and tight-lacing was in! There were also hooks and eyes at the centre front, known as a busk closure, for easier dressing and undressing. Although most corsets of the time would fit a waist of about 20 to 22 inches, these could have been extended by loser lacing, although there are also reports of ladies with waists of 15 to 18 inches.

The corset was worn over a cotton chemise and not directly next to the skin. The chemise was an unshaped short sleeved undergarment which reached just below the knees and had a drawstring neckline that could be adjusted according to the neckline of the dress. Calf length drawers with a back button closure (and open legged for convenience) were worn under the chemise, and were often decorative, with scalloped or embroidered hems. A corset cover was worn over the actual corset, and then the petticoats and crinolines were worn over these from the waist.

American cotton and bone corset and linen and metal (crinoline)cage c 1860 source

While many corsets were still sewn by hand to the wearer's measurements, there was also a thriving market in cheaper mass-produced corsets thanks to improved methods of manufacture, and particularly the invention of the sewing-machine. New materials such as spiral steel, that stayed curved with the figure, gradually replaced whale bone.

American cotton, metal and bone corset c 1861 and 1872 source

By 1860 there were already around 4,000 corsetieres working in Paris, and in London about 10,000 people were employed in the industry. In the English countryside another 25,000, mostly female, hands were employed, plus more in the steel industry in making metal eyelets. Until the colonies, America and Australia began manufacturing their own corsets, England, France and Germany competed against each other for the markets.

American cotton, silk, metal, bone, elastic corset c. 1885 and black corset c. 1893

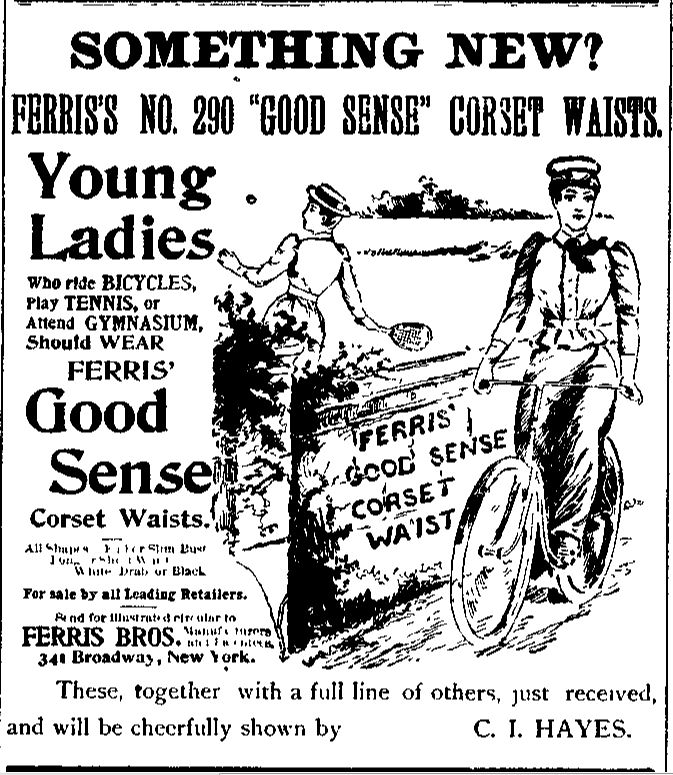

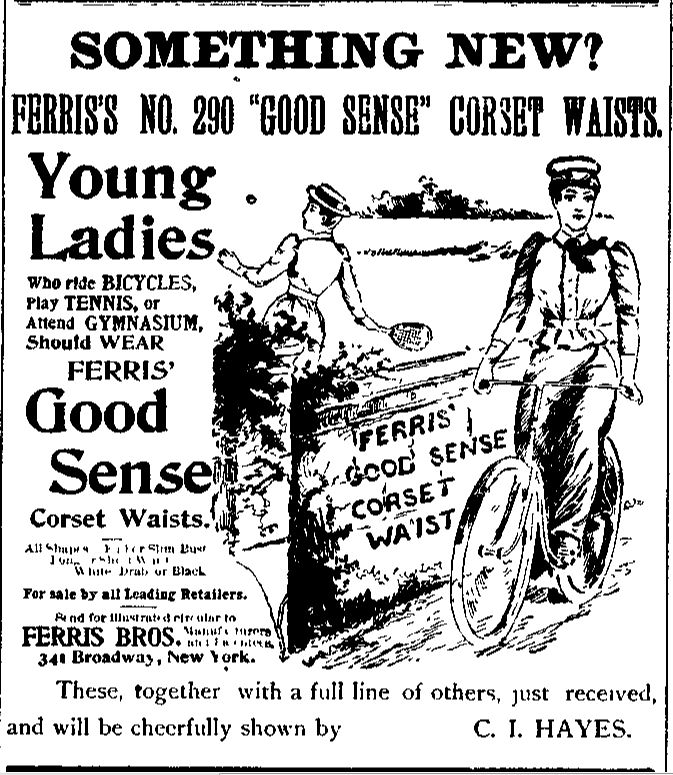

Corsets were worn by everyone, as the mass-produced article fell within reach of the working and rural classes. Not only women, but also by young girls and even children wore corsets, apparently so that they would learn correct posture. Corsets were worn during all activities, including tennis, bicycle and horse-riding.

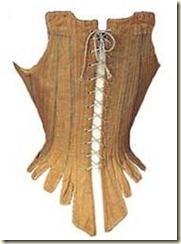

Riding corsets were "cut down" or shortened, particularly on the sides to make them more comfortable for riding. Much later on they also seem to be the first corsets to incorporate elastic panels for comfort.

Ad and a riding corset c 1870 source

Working-class women wore looser corsets and simpler clothes, giving them more freedom to move and do household chores or their often physical work, and they could lace their own corsets. The higher up in class a lady was, the more confining her clothes could be, as she had paid servants to do physical work, and also to dress her and tightly lace her corset.

British silk and cotton corset c. 1880 source European silk coset c. 1880 source

Corsets came in a variety of colours, including white, blue, black, charcoal grey, cream, yellow, burgundy, green and even red, and were often highly decorative and embellished, especially those of the higher classes.

An embellished corset in silk, cotton, metal, bone c. 1876 source French silk corset c. 1891 source

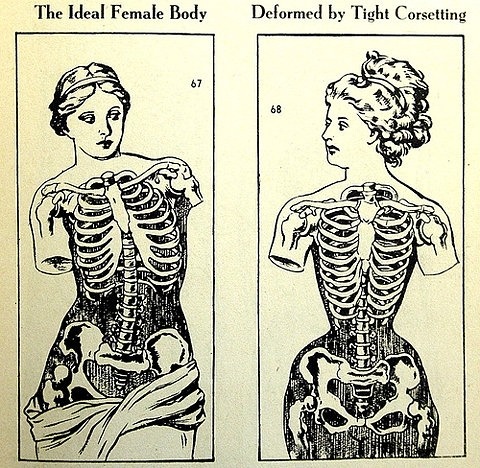

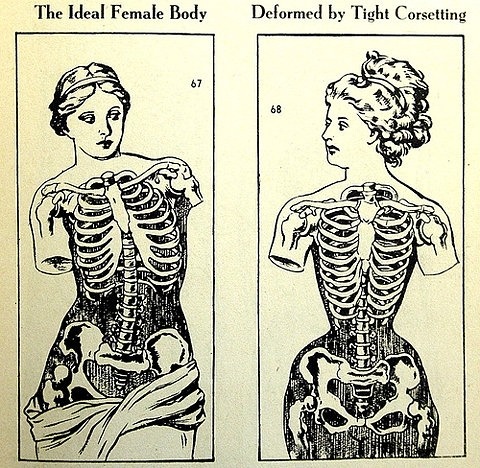

By the late 19th century, the dress reform movement that had began in the 1860s had taken it upon themselves to condemn tight lacing, although corsets themselves were still seen as necessary for beauty, health and posture. At a dress reform meeting in London in 1888, the speaker stated that women did not need corsets –as the Venus de Milo had not worn a corset. Queen Victoria reportedly replied that “Venus wouldn’t pass muster at a London Garden Party.”

Preachers, journalists and Doctors all joined in with tight lacing now viewed as vain, unhealthy and a sign of moral indecency. In reality, tight corseting was most likely the cause of indigestion and constipation (just like during pregnancy when your organs are all squished up and together), but it was commonly blamed for ailments such as hysteria and liver failure, lung diseases such as pneumonia and tuberculosis, and pregnancy complications due to compression of the womb (although there were separate corsets especially for pregnancy – and I really would have loved a corset while pregnant with twins!).

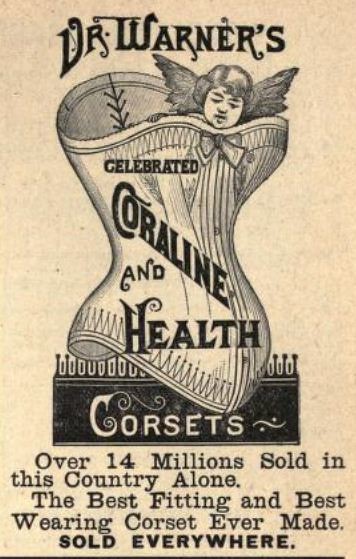

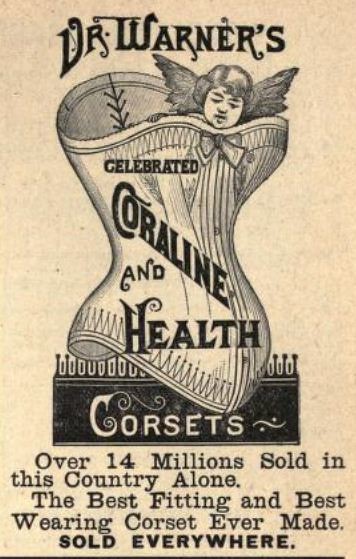

Doctors themselves began designing‘health corsets’. This corset below, by Dr. Warner's, includes cords (coraline) rather than the traditional bones to give structure, straps for extra support and aeration holes over the fully covered bust. Although to modern standards this still seems restrictive, for the period it was very advanced and in a sense, freeing.

Dr Warners health Corset, American, cotton, metal, bone, c 1890 source

A corsetiere with a degree in medicine, Inez Gaches-Sarraute, help to popularize the health corset. Also known as the straight-front corset, swan-bill corset and the S-bend corset, it was intended to be less injurious to wearers' health than other corsets in that it exerted less pressure on the stomach area , but it forced the torso and bust forward the hips back, creating an s-curve in the spine.

By the Edwardian era, around 1908, corsets began to fall from favour. I’ll look at those next time.

Deb xxx